Back in December, I had the privilege of talking to Bar Bruhis (KnoCommerce) and Will Holtz (SourceMedium) for the first edition of their Don’t V*LOOKUP podcast.

In the conversation, we got talking about some common pitfalls in data-led decision-making. There are quite a few cognitive biases we all fall victim to daily, but among the most prevalent in the day-to-day of growth marketing is survivorship bias.

To my surprise, this was a very eye-opening ninety seconds of conversation as I’ve since received a ton of comments from folks about the unknown (and now more understood) presence of survivorship bias in marketing organizations.

My experience with survivorship bias

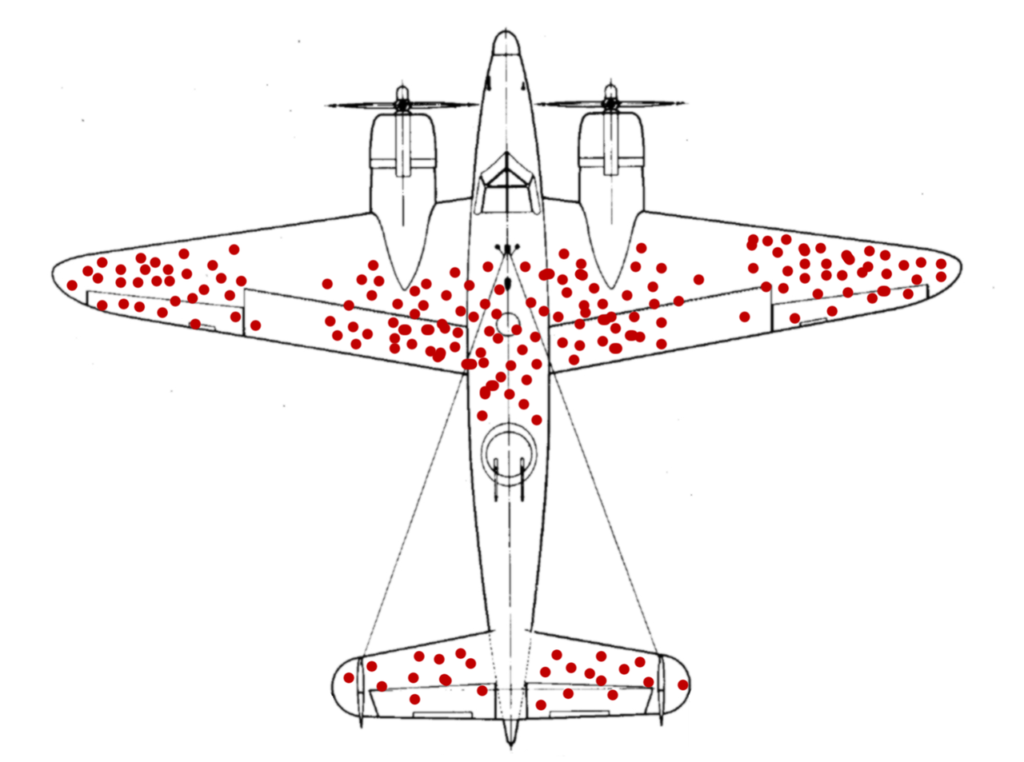

Once upon a (simpler) time, in a B-school course on organizational behavior, our professor split the class into groups and distributed a printout of a WWII-era fighter plane riddled with bullet holes.

He explained our task: the Army was hoping to get our feedback on where to reinforce the fighter planes that had returned from combat, based on where they’d been hit with enemy fire.

Red dots indicate bullet holes in the plane’s fuselage.

Without much thought about the sample we’d been given (fighter planes that had returned safe from combat), we got to work discussing the priority areas that we’d recommend reinforcing– largely based on the grouping of bullet holes seen on the plane in the sample.

A few minutes later, we presented our findings. Group by group, the entire class shared their thoughts on where these planes should be reinforced.

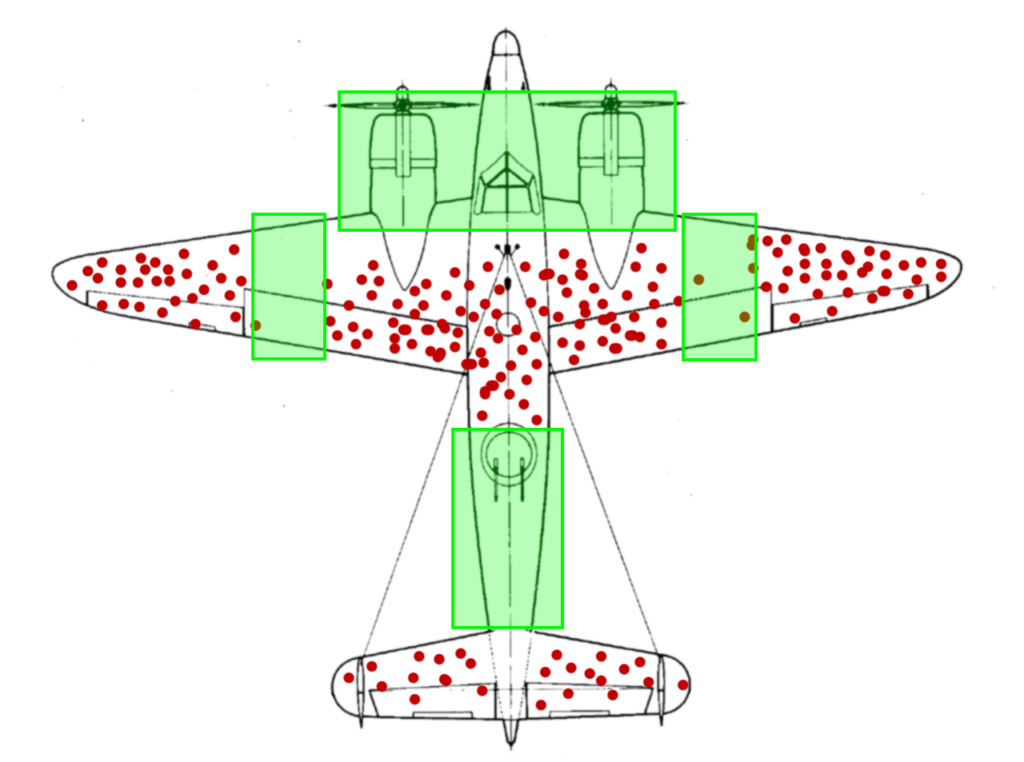

Blue highlighted areas representing the typical response of where the plane’s fuselage should be reinforced.

Each group agreed that the areas highlighted in blue (above) were the priority areas for reinforcement.

After the entire class had shared, our professor dropped the bomb.

We were all dead wrong.

Why spend time and resources reinforcing planes that had returned safe from combat? Surely, it makes more sense to figure out where planes that had not returned from combat should be reinforced. However, in that exercise, not a single one of the students (to the best of my recollection) called this out.

Those areas truly needing reinforcement would look something like the below (highlighted in green):

Green highlighted areas representing the correct response of where the plane’s fuselage should be reinforced. This assumes planes that did not return from battle were hit in these critical areas.

That, my friends, is survivorship bias. Optimizing on a sample of what’s already working (or, what’s survived) leads to more of what’s working without fixing what isn’t working (or, what didn’t make it).

Survivorship bias in a marketing organization

Most frequently, I see survivorship bias in customer surveying. Your goal is to gain an understanding of your customer base, qualitatively, presumably to cater your brand, products, and advertisements to those qualitative traits.

You launch the survey, and find that 75% of your customers identify as female.

Great! Clearly, your customers are predominately female, so you should create more more ads to attract female buyers and optimize your product assortment similarly.

Wrong.

For example’s sake, let’s say that 50% of the US population identifies as female. You’re indexing +25% in that population, and we can assume you’re indexing -25% in the male population (25% of your customer file identifies as male, when males make up 50% of the US population).

Your first instinct to optimize for what’s working is usually wrong (or at the very least, flawed). After all, you’re going to run out of female-identifying customers to convert at some point, while potential male-identifying customers are a blue ocean.

Challenge yourself and your team to ask: what’s not working? Why is that? What can we do to attract more male-identifying customers?

The longer survivorship bias persists in an organization, the more difficult it is to unwind. Using this gender example above, the longer you lean into female-focused customer acquisition, the more gendered your brand perception becomes. When this goes on for years, it becomes virtually impossible to reverse.

Of course, I understand that some brands and products are going to be gendered one way or another and that is fine! Don’t take this as every brand needs to be for everyone– that certainly isn’t the case.

Think of this example in other contexts: you see one of your ad hooks (value prop X) is performing really well, so you spin up more ads using value prop X. After a while, all of your customers have converted on value prop X, and no one is buying for value props Y and Z. Your brand/ product becomes known for addressing value prop X– and that’s it. You’re a one-trick pony. Solving value prop X is now your entire market.

The takeaway

Listen, I understand that in performance marketing and ecommerce we can’t say no to the money.

Scale what’s working, I totally get it; just don’t forget to get in a habit of questioning what’s not working (thinking about the difference between the entire population and your sample), hypothesize why, and dedicate some amount of time to testing those hypotheses.

If you’re interested in reading more about cognitive biases, I highly recommend the book Thinking, Fast and Slow by Nobel Prize-winning behavioral economist Daniel Kahneman.

Leave a Reply